Fluency is undergoing somewhat of a revival in England. It has long been the poor relation, the magnolia paint let’s say, of reading; a general stage the ‘typical’ reader will attain when s/he reaches about a quarter past seven years old. Prior to this, children are slow readers, they are laborious decoders; they are – after all – learning how to read. Or are they…?

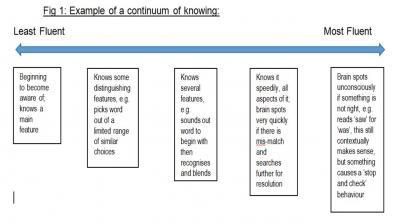

Don’t we already focus on fluency? Surely we aim for children to become fluent by, say, end of Year 2..? Well, one perception has been that children ‘become fluent’ after they have learnt how to read. In other words that whilst they are learning the myriad of GPCs, alternative spellings, and sufficient HFW they are bound to be slower readers. In fact children can, and indeed should, be fluently using their skills at any stage of reading. Think of fluency as a continuum, a sliding scale – rather like the old-school Hi-fi control sliders if you will. When a toddler is starting to recognise the golden arches of MacDonalds, at first the logo may need pointing out, then they may be about to shout out what it is just as the adult says, then they may get in there first, until finally they call out spontaneously ‘MacDonalds!’ In this sense, a really fluent recogniser would see an ‘m’ letter shape and call out MacDonalds, regardless of context. When a nursery-age child thinks they’ve recognised their name on a coat peg, when in fact it’s another child’s name, who just happens to share the same initial letter, they are at least fluently recognising a letter shape. This is known as the ‘logographic’ stage of reading (Frith 1985), and is a crucial step on the road to understanding and using phonics in the typical sense.

It’s like the NOFAN assessment principle (Never, Occasionally, Frequently, Always, Naturally), when we look for not just ‘frequently’, or ‘always’ using – say – full stops, but naturally doing so, to the extent it is effortlessly done and without need for proofreading. The brain is then freed-up to think of higher-order things, such as the content in writing or reading, for example, what I think the character is going to do next based on what has happened so far, things I know about him and clues the author has laid out about setting and time of day. I can connect, infer, and osmose into that world a little. Conversely, without fluency the brain is far too taxed to take in, retain and consider what is being read, let alone make inferences from it.

“Creativity floats on a sea of automaticity.” Pollard (2014)

But why is it so important? Isn’t fluency a desirable extra, something that’s more about entertaining an audience, performing and showing how much you understand about ’doing the voices’ than anything else? Wrong. It’s so much more. And it’s now been shown to actually help children become better decoders (Cunningham 1990; Whalley & Hanson 2006; Tunmer & Chapman 2012; Holliman, Wood & Sheehy 2012) and therefore potentially also has the power to reverse some types of literacy difficulties.

The commonly agreed key factors of fluency are:

- accuracy

- prosody/expression (pauses, intonation)

- automaticity (or rate)

One of the really effective ways of increasing capacity for retaining what has been read (in other words, comprehending) is to teach children to ‘parse’ their reading. This involves them ‘scooping up’ in chunks of meaning or phrases, and becomes especially vital the longer the sentences become. Teaching children to read in phrases of two, three or more words helps them to scoop up and load in swathes of meaning, without putting so much load on the memory, and helps the brain focus on the main ‘big picture’ elements. Readers who are reading at a word-by-word level are unnecessarily challenging their working memories and comprehension and will struggle to have capacity left to infer and deduce. Or…they may be ‘stuck in the mud’ with slow decoding/sounding out because they are under the impression that this is what we want them to do ALL the time. If after all that slow brain-work they can still retain what the message was, they are likely either doing this for our benefit or to keep control in their ‘safe zone’; they could probably cope with speeding up and should be prompted/taught to do so. (This is where easy-reads come in handy.)

One rather exciting thing that fluent reading does, is to get the brain ‘firing on all cylinders’. This means that for children with a poorer working memory, attention-span etc, who may be at risk of reading difficulties, this can help to effectively pump up those weaker areas. New, faster, stronger neural networks can be laid down making retrieval, organisation etc much easier.

“Neurons that fire together, wire together”. (Donald Hebb, 1949)

This is why some intervention support focuses on ‘over-learning’ so that knowledge and skills become habituated. Opportunities to revisit previously-read texts let you feel good about your successful reading and there is also something rather neurally clever about being able to unconsciously predict (not guess…deduce!) what is coming up. The eye and voice come together in space and time; brain pathways reach out to connect up, creating information superhighways.

But some children just read slowly… don’t they? What if there were some main, identifiable, controllable differences between more fluent and less fluent readers? What if more fluent readers tended to be given books to read that were generally easy to decode and therefore regularly had practice at becoming more and more automatic and accurate, while less fluent readers were given books that were too hard?

Number one controllable factor: check the book is the right match for decoding ability and therefore accuracy (NC 2014, Ofsted 2014). A quick Running Record/Miscue Analysis carried out by the class teacher will identify not only whether the book is the right match but also (crucially) the next steps for precision teaching, foci for guided/individual reading etc. For more information on this valuable tool, see PM Benchmark Kit, and further guidance on matching texts in the HfL Guided Reading booklet.

National Curriculum 2014 is clear: if word reading is below age-related then children must be helped to catch up quickly, including using closely-matched texts. They are still taught age-related comprehension skills in whole-class situations, and on the texts they read, but the texts they read must be closely matched. This can mean taking the decodability/difficulty level down a notch or two. Don’t worry. Trust what you know about learning and you will see them ‘prune back to steam on’, as they remember what it feels like to understand, enjoy, successfully problem-solve and to regain some automaticity. For some children this simple revelation unlocks the ‘thrill’ and ‘will’ needed to improve the ‘skill’.

Number two controllable factor: emphasise, and teach, aspects of prosody…

“The book is talking to us.”

I can still remember so vividly the conversation that really brought the Simple View of Reading to a new reality for a vulnerable six-year-old reader. He had done a good job of decoding, even working well on alternative pronunciations, but it was still mud-like, waiting for the book to tell him the answers. He had grown from depending on others to help him, to now the book; he needed to know he already had every resource he needed within him to be a successful, active, reader. My targets for him: to re-read, putting it all together, pausing at punctuation and adding more lilts in his voice for the longer sentences to make sense.

“Does that make sense?” …led to a confused face.

“What would you say if it was you?”…still confusion.

“The book is talking to us. If you were the book, how would you say this?”

He got it. He knew what I meant. His eyes widened though, as if I had asked him to disobey a school rule. He had sounded out, he had told me what the words said, but that seemingly wasn’t enough for this rather persistent pedant sat next to him right now. Glancing up at the print-out of Superman with his laser vision from our early focus on steady eye-pointing, he looked at me and had another go. Better.

Okay. Time to get radical. I covered the book and had him repeat the sentence after me, phrase by phrase, rehearsing the voices, lilts and swoops. The spark grew in his eyes. With a warmed-up oral rehearsal fresh in his mind I revealed the page.

“Try that again.” I said.

Whoosh. Scooping almost in hesitant disbelief at times, he read. He went on, gobbling up the page as if it was a feast of tumbling visions and no longer words. For a moment we were there in the book in that moment with the character.

Number three controllable factor: increase opportunities for developing automaticity.

“Easy reading makes reading easy.” (Tim Rasinski)

When re-reading texts or reading easier texts, children are then freed up to comprehend, infer, internalise new vocabulary encountered etc. It has also been shown – along with letter-name knowledge – to have huge correlation with spelling accuracy. Brooks (2013) showed that a fluency and comprehension-focused intervention had a bigger impact, especially for disadvantaged children, on spelling ability at Y6-7 than one based on discrete phonics alone.

“Spelling and reading build and rely on the same mental representation of a word. Knowing the spelling of a word makes the representation of it sturdy and accessible for fluent reading.” (Catherine Snow et al, 2005)

Other ideas for developing automatic decoding and improving rate or pace:

- Repeated readings of books or passages (could be timed)

- Take turns reading page/sentence etc so they hear a fluent model

- Reader’s Theatre/playscripts

- Poetry reading

- My turn, Your turn – get them to repeat a sentence the exact way you read it, and if it’s not the same, re-model and ask again. Get them to reflect: “Did you sound good to listen to?” “Did it sound like talking?”

- After decoding ‘work’: “Now put that all together so it sounds smooth/good to listen to/like talking.”

- Encouraging decoding into chunks before going down to individual phonemes, e.g. use of syllables, morphology

- Finger frame a line: “Read to here, like talking.”; “Make it sound good to listen to.”

- Have them use a Speech and Language Therapy ‘phone’ (try TTS) so they can hear themselves amplified. [These can also be good for those struggling to sound out when spelling, e.g. confusing vowel sounds.]

- Try recording them and playing back for review as above

- Practise spelling words that were hard to read, and will occur again frequently. If using a ‘Look, Say, Cover, Write, Check’ method, ensure you have them look for the tricky bits and self-check after each go.

References:

Bodman, S. & Franklin, G. (2014). Which Book and Why? Using Book Bands and boo