Ofsted looming can feel overwhelming, and we know all our colleagues are feeling the anxiety too. As the leader of a core subject, like mathematics, none of us want to get it wrong and we want to know we have reflected our school in the best possible light.

Ed Farrell, the maths subject leader from Cowley Hill Primary School in Borehamwood felt sure this was the year for their turn and started to make plans for September. Here he shares his experience which, to his surprise, he found very valuable and almost “enjoyed”!

Last academic year, in preparation for learning in September, we took note of the DfE guidance “Teaching a broad and balanced curriculum for education recovery” (DfE July 2021):

When deciding what to teach to support education recovery most effectively, leaders can help all pupils by focusing on making sure they are fluent and confident in the facts and methods that they most frequently need in order to be successful with further study.

In the context of missed education, it remains crucial to take the time to practise, rather than moving through the curriculum content too quickly. What pupils already know is key. Progressing to teaching new content when pupils are not secure with earlier content limits their chances of making good progress later.

The sequence of teaching mathematical content is also very important: gaps need to be filled before new content is taught.

We had already been using HfL Back on Track resources. Included with these was a complete set of diagnostics and so we were able to be precise about key concepts for each year group and the gaps in children’s learning.

You may be interested in a recent blog by a Year 5 teacher who explains how he used it with his class: Getting back on track in primary maths – tracking back to build up.

We knew that to support the progress of pupils, the acknowledgment of potential gaps in learning and the subsequent careful navigation forwards would be key, alongside being confident in assessing when pupils were ready to progress.

The identification of gaps was (and continues to be) a team effort. Leaders and class teachers work collaboratively to agree which strands of maths may, or may not, have been secured; in its infancy, this process began as identifying which strands teachers would revisit with each year group if time was not an obstacle. Yet with the pandemic, it evolved into a robust process, pulling the teaching team together to collaborate in support of a curriculum that considers and acknowledges gaps in learning and allows time for action to close them.

The most recent version of this process involved acknowledging that content taught remotely, at any point in the last three academic years, had to be carefully weighed up as the reality of suggesting that something had been ‘secured’ remotely, was not something that could be done with great confidence.

Further to this, content taught face-to-face had its own disruptions (attendance (of both pupils and staff), restructuring of the day to accommodate bubbles amongst other measures and timings etc.) and therefore also had to be considered carefully.

Stemming from this analysis, we identified and categorised the outcomes as follows:

- those where the majority of pupils had secured the outcome statements and were ready to progress;

- those where further intervention (through fluency sessions and main teaching) was necessary to support progress to ensure that students were ready to progress; and finally,

- those where the exploration was deemed to have been too limited and would likely be required to be taught as new learning rather than a progression of skill or reactivation.

Using the identified gaps, the priorities for each year group were sequenced, whilst simultaneously weighing up missed opportunities as well as future opportunities. Future opportunities identified and the need and manner for expansion to accommodate the missed prior opportunities was agreed and logged. This was conducted whilst also keeping a clear focus and awareness upon the age-related outcomes, as this in turn would, and has continued to, challenge and raise the bar for lower attainers.

With the curriculum mapped, and a new course for the current academic year plotted, staff were then supported and led to identify (using the maps) areas where reactivation of prior learning would be required as pre-steps before the expected age-related sequence of learning could commence.

For example, our current year 6 cohort had limited exposure and opportunity to develop and strengthen their understanding around area and perimeter, including the relationships within. To support this identified gap, early intervention was implemented with the intention being to re-activate prior knowledge. In some cases, this meant recalling teaching from the year 4 curriculum.

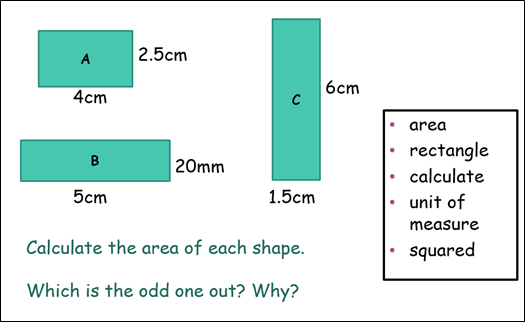

Using fluency sessions, short, sharp, yet frequent opportunities encouraged the accurate use of previously taught vocabulary. The beauty of these short sessions lays in the ease of repeating a skill through simple and fast editing of previously used materials. The following examples firstly demonstrate the initial session where the formulae of area was revisited and reactivated for fluency in recall; the calculation was reasonably straightforward (namely to support the promotion of mental fluency).

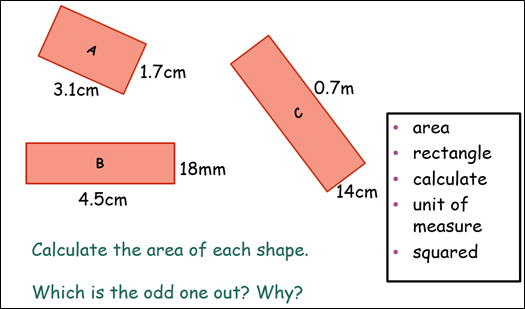

With the process now re-explored, in the next revisit, the task has not varied; focus is still upon the concept of calculating area and differentiating between the examples. The placement of the shapes varied which fed conversation around the length/width despite the orientation of the shapes. The unit of measure was also varied to include decimal notation – another area where children had limited security at the end of the previous academic year, as noted within the curriculum mapping outlined previously.

Moving ahead, with the pre-teaching conducted through the fluency sessions, the sequence of learning around the relationships between area and perimeter began with an additional opportunity for pupils to demonstrate their current level of understanding.

Making the best use of time

The benefits of our spiral curriculum had been compromised to some extent, where some outcomes and even entire strands had not been previously explored. Yet this is where the fluency sessions come to aid. Our ongoing fluency foci allow for pre-teaching to be embedded in support of overcoming the barriers and some of the excessive gaps presented in the pupils’ learning. Short, sharp and frequent exploration allows for reactivation of prior learning, some of which had not been called upon for durations in excess of a single academic year (an example would be the exploration and securing of telling the time and confidence and fluency over the units of measure involved; first explored in KS1, the year 4 cohort had received very limited opportunities).

Highlighting links between strands allowed staff to exploit them in a manner that benefits the pupils. Despite the initial (and momentary) increase in workload, the necessity to amend the maths curriculum was just that, and progress in knowledge and understanding of pupils in all cohorts would have been considerably hindered if we hadn’t done it. This, in turn, would have subsequently created an even greater increase in teacher workload stemming from what could have been an endless cycle of backpedalling and the burning of time we simply do not possess. Staff are encouraged to make the best use of time for we cannot create more, yet we can use it creatively. We ensure that the pace of teaching is not increased in a manner that could create a greater number of ‘stragglers’; instead, our ethos has remained clear and crucial:

deeper learning takes longer yet lasts longer and creates a far more secure understanding for problem solving.

Short inspection – 12 July 2016

Our school’s previous Ofsted report noted that the next steps and ongoing focus should include attention to ensuring that ‘higher-attaining pupils are consistently challenged by all adults, so that they achieve the very best they can in writing and mathematics’.

Our school’s previous Ofsted report noted that the next steps and ongoing focus should include attention to ensuring that ‘higher-attaining pupils are consistently challenged by all adults, so that they achieve the very best they can in writing and mathematics’.

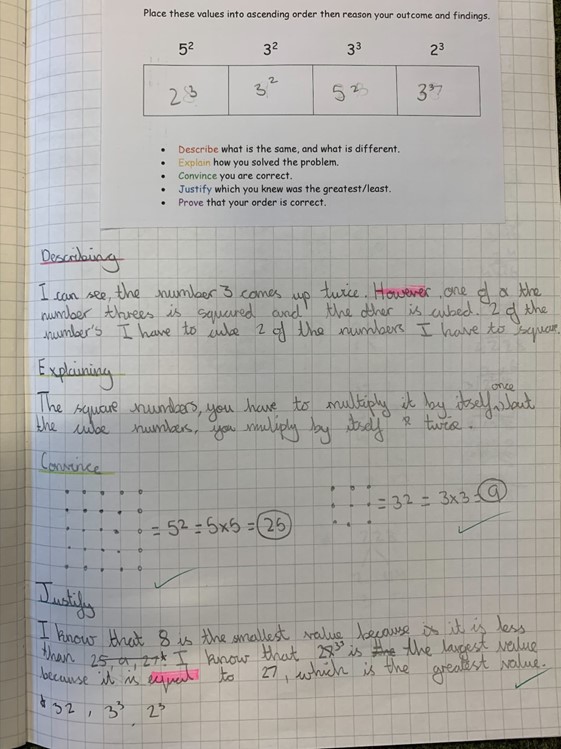

The level of challenge provided, whilst initially focussed upon the higher-attaining pupils, has since evolved into a robust curriculum where all children are consistently challenged in all year groups. Substantial time was placed into the development of reasoning across the entire curriculum; pupils are challenged to describe, explain, convince, justify and prove their findings.

School inspection – 05 and 06 October 2021

With the pandemic, the current intentions include the necessity to support the curriculum recovery.

Our reasoning thread has been a key factor of doing so and was positively highlighted during our recent inspection. Children in a range of year groups were observed being asked to convince or justify their findings, as opposed to being directed to check in response to an error – in doing so, pupils self-corrected and subsequently demonstrated the depth of their understanding, providing valuable input for teachers’ ongoing assessment for learning.

The implementation of our spiral curriculum was praised, namely where adjustments were made and justified with outcomes supporting the decisions. A thorough dive into the curriculum mapping process previously detailed noted ‘where pupils are coming from, currently at, and heading to’ as being vividly clear to leaders and teachers alike.

My actions as a leader were placed under the spotlight when it came to effectiveness of leadership; the key to success here was honesty around strengths and areas for development. To ensure consistent, highly effective practice, ongoing monitoring is a part of our school life. I have adopted a democratic style in which my leadership is participative; it is far from finger pointing and rule reader.

Instead, throughout ongoing monitoring, areas for development are highlighted and discussed with staff in need. Following this, agreed actions and support provided are logged within a proforma where a two-week cycle is stated. The impact of agreed actions is then reviewed and discussed further. The outcome of this was highlighted within the inspection, under the impact and awareness of leaders within the school and complimented by some members’ recounts of the support for professional development provided. Whilst there may be a temptation to refrain from detailing areas for development within your school, I cannot stress the need to avoid doing so enough. Leaders lead; the inspector was keen to see how and identifying need for development is a major part of that responsibility.

The ‘doom and gloom of Ofsted’ is not something that was experienced during the recent inspection. Maintaining confidence in the actions taken, clear articulation of said actions, alongside an explicit vision for what is next, made the duration of the inspection a positive experience, rather than one many would label as undesirable.

The inspector’s questions were fair and reasonable, far from the hearsay of trying to ‘catch us out’. My conduct, effort and application as a leader, as well as those of the teaching staff, are all done for a common goal, the children.

Inspections can feel like a personal investigation into action taken (or not taken) although knowing why, how, and when these were taken proved to be valuable. On reflection, the entire experience was a recital of the consistent effort made in school to provide what we feel is a strong, purposeful curriculum that evokes free-thinking, able, confident problem solving.

If writing a ‘survival guide for inspections’, I would condense my experience into three key points:

Confidence

Decisions made are meaningful and discussed in a collaborative manner prior to implementing them. Acknowledging what has not necessarily been as successful as envisioned was respected and noted by the inspector as much as what had. They were keen to hear how decisions were made, why and (most importantly) what the impact of these was. Knowing the story of how we arrived at the point we were at during the inspection removed any potential weight from my shoulders. Maintaining confidence and conviction whilst articulating action taken relaxed not only myself, but the inspector.

Whilst on the topic of confidence, it would also be worth mentioning the necessity to be able to honestly highlight the strengths and areas for development in your setting. Noting areas of previous concern and action taken reaffirmed the effectiveness of leaders in school, as well as the commitment to development from teachers; ultimately, the pupils are at the forefront of all decisions made and this is what the inspectors need to be sold on.

As with many other inspections I have heard about, inspectors state when meeting the staff prior to commencing the inspection that the team should ‘continue as normal’ and I wholeheartedly agree. Deviating from usual practice stands out from a great distance – confidence is essential for all members of the team whether being interviewed and/or observed.

Articulation

Being able to clearly articulate was another key element. Practise using likely/common questions with your team – question your teachers and support them in being as clear as possible in their responses; have others question you also.

We held conference as a staff in the months prior to the inspection where questions were put out and we conferred on our responses – we were all telling the same story, yet some responses were buried amongst verbiage that ultimately led to deviation from the facts and the impact our efforts have had and are having. Leaders or not, we are all accountable and ensuring that all staff members are aware of this is not to create a sense of anxiety, but to encourage an environment where expectations and standards are consistently high for all.

It is also worth highlighting the need for honesty here again – inspectors are not looking to trip you up, nor catch you out; they are looking for confidence in your practice and vigilance in decision making.

Awareness

As a leader, this was the largest and most important part, yet largely stood upon the pillars of confidence and articulation.

Why have you made the decisions you have? What is/was the impact of these? Why is your curriculum in its current state – what has led you to this point? What are your next steps? What are the strengths of not only your curriculum, but your teaching staff? (Be honest!)

Overall, in my experience, the inspection was an enjoyable and considerably invaluable experience that was far from the labels of pressure and anxiety it has come to be so widely associated with. Ultimately, it became a platform to celebrate the commitment, achievements and dedication of the staff who collaborate to create and deliver the curriculum which develops the minds of tomorrow.

Subject leader toolkit for mathematics

Blog authored by Ed Farrell, Maths Subject Leader at Cowley Hill Primary School.